There is a void here in Los Angeles, a space that feels inexplicably hollow. The city of dreams isn’t shining quite as bright these days. For those of us who pilgrimaged here to make movies, 2025 was supposed to be our return to form. We, the headstrong survivors, were told we’d be met with opportunity if we simply endured. And so we have—survived ’til ’25. That was the refrain echoed from every Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf in Highland Park to every sushi bar in Little Tokyo.

After a once-in-a-century pandemic, historic labor strikes, and unprecedented contraction in production, this was supposed to be our year to get back to the making of dreams. Instead of waking New Year’s Day to the pearly gates of Paramount swinging open, we awoke to our city burning to the ground. And now, just last week, we received word of the passing of one of our greatest artists — David Lynch.

I was first introduced to Lynch’s work in the early 2000’s via the film library at TCU in Fort Worth, Texas. That’s where I began my undergraduate film studies after kindly being asked to leave the Studio Arts program, where I was studying painting and graphic design. In the back of the south side of the Moudy Art Gallery, there was a vault filled with countless laserdiscs, VHS tapes, and DVDs. At some point in my first year, I got wind they were looking for librarians. I leaped at the opportunity. Nobody really frequented the library. I have no idea why. It was a treasure trove of cinematic history, and I knew if I got a job manning the desk, it meant I’d mostly be left alone to watch movies all day. Which is exactly what I did.

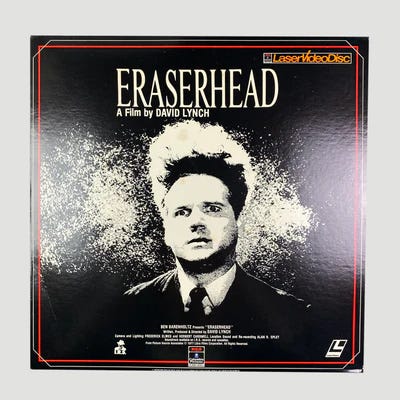

One day, while thumbing through the laserdiscs, I came across a copy of a film I’d never heard of by a filmmaker I only vaguely associated with another movie, Mulholland Drive—which I had also never seen. What hooked me about this laserdisc, in particular, was the cover. It reminded me of the punk albums I used to buy back in the 90’s when I was discovering bands like Descendents, Operation Ivy, and Fugazi. It was nothing but a stark black-and-white image of a man with a stunned expression and wild, unkempt hair. What looked like chalk dust floated all around him, backlit—it resembled an explosion. “What the hell is an Eraserhead?” I surly pondered.

I don’t know why, but something about that cover art piqued my curiosities. I popped it in and took in the strange wonders of Eraserhead, Lynch’s 1977 debut. It didn’t take long to realize everything about that film was explosive.

Now, contrary to what you might assume, I wasn’t enamored with Eraserhead. It wasn’t punk at all; it was a gonzo bit of surrealism. It was a nightmare—indescribable, illogical, confounding, and strange. In truth, I despised Eraserhead at first. Why? Because it frustrated me. It made me uncomfortable. It didn’t look like a movie—at least not the movies I loved. It didn’t play by the rules of filmmaking that I had grown comfortable with and that mostly perplexed me.

And yet, no matter what I did, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. For weeks, the images lingered with me. I began researching Lynch feverishly. I discovered, like me, he was from a small town (Missoula, Montana) in Middle America, and, like me, he left that small town to go to art school, starting in painting before transitioning to film. This information was rocket fuel. You have to understand, back then, before social media, finding a road map to a film career when you were growing up in the middle of nowhere was virtually impossible. In David Lynch, I saw a kindred spirit with a blue print for a career.

I went through a Lynch run after that, watching Blue Velvet, Lost Highway, Twin Peaks, and his version of Dune. I even rewatched Eraserhead. The more I watched, the more I saw a method to the mania. I began seeing Lynch’s films not as traditional narratives but as paintings—extensions of Lynch’s dreams. Understand that, up until that point, I had grown up on Spielberg, Lucas, and James Cameron. American independent film at the time was whatever Sundance had given us. Back then, it was Tarantino, Soderbergh, and Kevin Smith, which I devoured. I had probably dipped my toes into the French New Wave, and I’d definitely seen some Bergman by that point. But Lynch was my first exposure to a version of American arthouse that pushed boundaries I didn’t even know existed until Lynch showed me the goddamned demarcation seven thousand miles past everything else I’d ever seen in my life.

After finishing college, I packed a bag, loaded my black Labrador Milo into my Jeep, and drove directly to Hollywood knowing not a single person. I don’t know that I realized it then, but Lynch was who I wanted to be. I didn’t want to make the same types of films, mind you, my dreams weren’t nightmarish surrealism. Still, I did dream of approaching filmmaking much the way he did: writing scripts in greasy L.A. diners by day and making offbeat character-driven movies on my own terms by night. Lynch seemed to embody that romantic balance of working outside the Hollywood system yet also accepted by it.

That balance, I’ve since learned, is a high-wire act that few can achieve. Lynch did it because he was fiercely himself—and, let’s be honest, fiercely cool. You just can’t manufacture that. I recall hearing a story about George Lucas bringing Lynch in to potentially direct Return of the Jedi. As Lucas pitched Lynch the movie, showing him Wookiees, Ewoks, and all manner of furry creatures, Lynch developed a headache. By the end of the pitch, that headache had melted into a full-on migraine. He ended up hunched over in a phone booth down the street, telling his agent there was no way on Earth he could ever make a Star Wars movie.

That’s David Lynch, folks. For us, that opportunity would be a dream come true. For him, it was a nightmare.

In his later years, Lynch became a patron saint of the city he loved, transcending his notoriety as just a filmmaker. His weather reports became must-listen morning radio before transitioning to YouTube, where he’d shout, “Can you believe it’s Friday once again?” in his sharply optimistic transatlantic accent. He’d often end his sunny reports with his hopeful hallmark: “Blue skies and golden sunshine all along the way!” In the last few years, his punchy, acerbic quotes about filmmaking have become Instagram fodder, and his existential philosophies on spirituality and art took on a near cult-like status. But with Lynch, it never felt like self-aggrandizement. It was always about the art—and the sanctity of self-expression. “Keep your eye on the donut, not the hole,” he’d say.

Beyond filmmaking, Lynch dabbled in all the arts. Here’s my signed copy of Lynch’s book Naming, a collection of his photographs and mixed-medium pieces, I recommend.

He was also a capable musical artist, ranging from haunted rockabilly to sparkly, unctuous collaborations with Chrystabell. Every work he created was interesting, if not deeply personal. But none reached the stature of his cinematic oeuvre. That’s where all his artistic selves filtered down to their most resonant, perplexing, and inspired.

Those two words—perplexed and inspired—are how I’ll always think of Lynch. If you asked me which of his works was my favorite, I’d struggle to answer, I’d probably say Wild at Heart, but I’d struggle. Honestly, it wasn’t even about his work. It was about him. It was about the mysterious alchemy of his personality and persona. That’s what Lynch was and what my favorite artists are. Perplexing and inspired.

How ironic that as we watch our city burn to the ground, we mourn the loss of David Lynch. It feels like something Lynch himself would have conjured from his dreams and brought to vivid life on screen. Something in me thinks Lynch, ever the optimist, would see this moment as a rebirth or a evolution into some new era. He had lots to say about time. Maybe it is. It’s hard to be optimistic right now looking out my window.

In my mind, I see David. He’s wearing his white chambray button-up and black sport coat. His wild gray hair wriggles in every direction. He’s got a cigarette in one hand, a chocolate milkshake in the other, and he’s leaned back in a red vinyl booth at the front window of Bob’s Big Boy in Burbank. His eyes are obscured behind a pair of Ray-Bans and there’s a mischievously contagious smile on his face. But it’s not David anymore. Now it’s his ghost. And for filmmakers like me, that specter represents the passing of an era of independent filmmaking we’ll never get back.

Best of luck out there in the great beyond, Mr. Lynch.

And thanks for sharing your dreams with us.

Great write up. Also on a Lynch run here. Subscribed

Love this